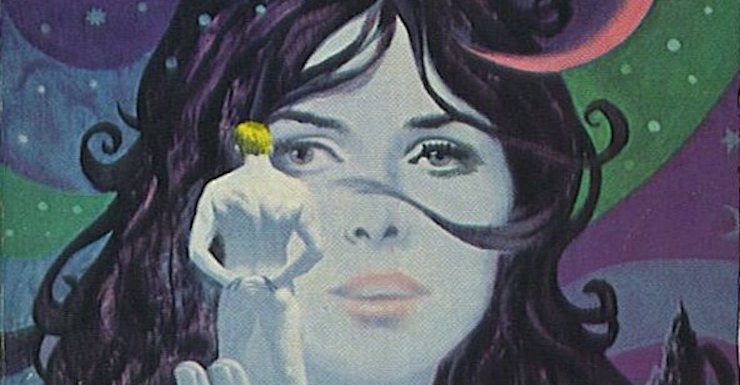

I recently reread three thematically similar books: Poul Anderson’s Virgin Planet, A. Bertram Chandler’s Spartan Planet, and Lois McMaster Bujold’s Ethan of Athos. All three imagine single-gender planets: worlds whose populations are either all men or all women. This particular selection of books to reread and review was mere chance, but it got me thinking…

There are actually quite a few speculative fiction books set on single-gender planets (in which gender is mainly imagined in terms of a binary model) 1. Most of them are what-if books. As one might expect, they come up with different extrapolations.

Some single-gender planets are near-utopias; humans manage quite well with just one gender, once reproductive solutions are in place.

- Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland and James Tiptree, Jr.’s “Houston, Do You Read” suggest that the world can get along just fine without the missing gender. In these cases it’s men who are superfluous.

- Bujold’s Ethan of Athos depicts a world without women, one which also seems to work fine. Mostly.

Perhaps a world might actually be better off without the other gender:

- The Joanna Russ short story “When It Changed” posits that the sudden reappearance of men is a terrible tragedy for the isolated world Whileaway. Pesky men.

- A great many of Bujold’s Athosian men agree that they are much better off without those pesky women.

Some planets demonstrate that even if one gender is eliminated2, a single gender will display the full range of human frailties.

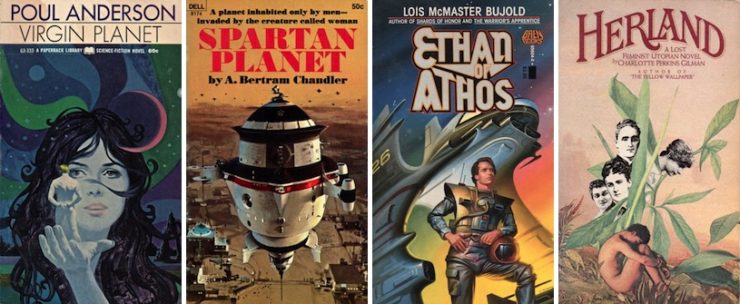

- In Nicola Griffith’s Tiptree and Lambda Literary Award-winning Ammonite, folks is folks.

- Ethan of Athos might also fit again, here. Athosians may have fled the dreadful temptations of womankind, but they cannot escape human nature.

Other authors have set out to prove that difference is the spice of life.

- The men of Spartan Planet have, in the absence of women, devolved into brutes. Their idea of fun is getting drunk and punching each other in the face. I think there was a sequel, with women, which I have long since forgotten. I suspect that life may have improved, but not completely. (Because without a problem, how can you have a plot?)

There are books in which gender differences are funny. Slapstick funny.

- In Anderson’s Virgin Planet, our hero, David Bertram, discovers that being the only man on a planet of beautiful women can be daunting. The women have imagined the long-lost men as heroic creatures. David Bertram is… not.

A number of the unigender worlds have caste-based social systems, presumably inspired by the social arrangements enjoyed by ants and bees.

- Again, Virgin Planet is a fine example: each family is a clone line, with known strengths and weaknesses.

- Neil Stephenson’s Seveneves is much the same, although in that setting, deliberate variations have been introduced.

- David Brin’s Glory Season does not quite eliminate men (although they are relegated to secondary reproductive status), but the parthenogenic lineages are, like those in the Anderson and Stephenson books, known quantities with established specializations.

Another, unfortunately large, category of unigender worlds consists of those novels in which the author has seemingly forgotten that the other gender exists at all. The absence is not intended to make some point, but simply because the author neglected to include any characters of the missing gender, even as supporting characters3.

- The novels of Stanislaw Lem are very low-grade ore when it comes to finding women characters. Lem’s protagonists often struggled to communicate with the truly alien. Judging by the dearth of women in his books, however, women were too alien for Lem.

- Perhaps the most remarkable examples come from Andre Norton books like Plague Ship, in which women are completely and utterly missing even though the author was a woman and presumably was aware that women existed4.

These unigender settings can be distinguished from the what-if books because the question “why is there only one gender?’ is never raised or answered. Whereas the what-if books generally explain exactly why one gender is missing.

It should also be noted the missing gender in such books is usually female. This isn’t an accident. It must have something to do with the perceived audience for SF being young men (presumably unacquainted with women or why would they have time to read SF?). Olden time authors also tended to have firm notions as to what kind of story might be genre-appropriate: if SF is about scientists inventing things, or can-do he-men having adventures, well, that’s not what women do. To quote Poul Anderson’s “Reply to a Lady: “The frequent absence of women characters has no great significance, perhaps none whatsoever.” It’s just that authors like Clarke and Asimov “prefer cerebral plots (…).” It’s not that women cannot feature in narratives—however, proper SF narratives concern thinking and doing important stuff. Women don’t do that sort of stuff, so far as Anderson was concerned. Curiously, Anderson seems not to have been rewarded for this reply with the rousing accolades he perhaps expected…

There has been, to my knowledge, only one novel ever published in which men are completely absent and where the author feels no need to explain where the men went: Kameron Hurley’s The Stars Are Legion. Which came out at in 2017. So, plenty of untapped genre potential here!

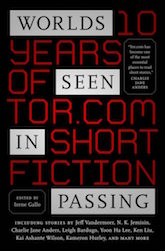

Buy the Book

Worlds Seen in Passing: Ten Years of Tor.com Short Fiction

1: Disclaimer: I know that there are many variations on gender, and that sorting people into two hard-and-fast categories does violence to biology, psychology, culture, and individual choice. But authors–even authors of SF—have often defaulted to binary conceptions of gender, although that is evolving in more recent years.

2: Officially. In some cases, and to say which cases would be a spoiler, it turns out the world had the supposedly absent gender all along. This at least helps explain where the babies are coming from, although uterine replicators, clone vats, and vigorous, sustained handwaving can also serve.

3: Tangentially connected to SF (but not actually SF so I cannot use it as an example in the main text): Harry Stine’s The Third Industrial Revolution manages to wrestle with the weighty matter of population growth without ever mentioning women.

4: Norton is an interesting case because despite contributing to the issue herself (or perhaps because she contributed to it), she was well aware that women were curiously absent from speculative fiction. From her “On Writing Fantasy”:

These are the heroes, but what of the heroines? In the Conan tales there are generally beautiful slave girls, one pirate queen, one woman mercenary. Conan lusts, not loves, in the romantic sense, and moves on without remembering face or person. This is the pattern followed by the majority of the wandering heroes. Witches exist, as do queens (always in need of having their lost thrones regained or shored up by the hero), and a few come alive. As do de Camp’s women, the thief-heroine of Wizard of Storm, the young girl in the Garner books, the Sorceress of The Island of the Mighty. But still they remain props of the hero.

Only C. L. Moore, almost a generation ago, produced a heroine who was as self-sufficient, as deadly with a sword, as dominate a character as any of the swordsmen she faced. In the series of stories recently published as Jirel of Joiry we meet the heroine in her own right, and not to be down-cried before any armed company.

Norton decided to address this issue herself. What was the reaction, you ask?

I had already experimented with some heroines who interested me, the Witch Jaelithe and Loyse of Verlaine. But to write a full book (The Year of the Unicorn) from the feminine point of view was a departure. I found it fascinating to write, but the reception was oddly mixed. In the years now since it was first published I have had many letters from women readers who accepted Gillan with open arms, and I have had masculine readers who hotly resented her.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviewsand Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.